We’ve all heard the rhetoric. “We need to take America back for God!”

Why? Supposedly so we can regain some bygone level of ethics or moral standards. Supposedly, if we don’t, God will get tired of us “rebuking” God and remove God’s hand of protection from us. Supposedly so God won’t test us or judge us or something.

Yet, as Gregory A. Boyd notes in his important book The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power Is Destroying the Church

Yet, as Gregory A. Boyd notes in his important book The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power Is Destroying the Church, taking America BACK for God assumes we, at one time, really belonged to God, followed God, listened to God. Boyd goes on to ask, when was this glorious age in the history of the USA?

Let’s start way back. We’ve been taught that many people migrated to North America for religious freedom. So was this glorious time when some of our forebears imprisoned, tormented, and / or hanged many suspected to be witches? Is that what so many want to take us back to?

Many of our European forebears believed that God (or nature) had sanctioned “manifest destiny” for white Christians to conquer North America. So, was this special time when white aliens made and broke treaties with the Native Americans and forced them out of their homelands? Is that what so many want to take us back to?

One of the things that helped the southern states of the USA to thrive economically early on was the inexpensive labor provided by African slaves who were seen as 3/5 of a human. So, was our land glorifying God when it continued to allow and support the slave trade and the ownership of slaves? Or, was this golden age when our nation decided to take up arms against itself in the Civil War? Is that what so many want to take us back to?

Maybe the golden years were when Jim Crow laws were enforced and “separate but equal” facilities were seen as okay. Maybe it was when so many worked hard to suppress the vote of African Americans. Is that what so many want to take us back to?

Speaking of voting, for the first 144 years of our nation, women were apparently not seen as being “created equal” with “all men.” Apparently, they, prior to 1920, had not been “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” like voting. Even today, women tend to make less than men in comparable jobs. Is that what so many want to take us back to?

Was this age that many want to take us back to before there were child labor laws? Was it before workers’ compensation protected people? Was it before laws were enacted to limit the amount of hours that companies can force people to work? (I mean, who really wants to give up their weekend?). . .

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

It seems that many who want to take us back to whatever complain that politicians don’t use the words “God” or “Jesus” or “Christian” or whatever. “People are just trying to take God out of everything,” I hear again and again.

It seems that many who want to take us back to whatever complain that politicians don’t use the words “God” or “Jesus” or “Christian” or whatever. “People are just trying to take God out of everything,” I hear again and again.

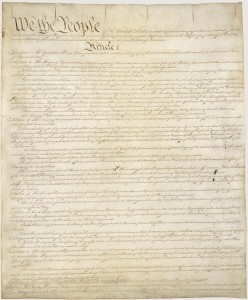

Some of these same people say that not only do we have to get back to God, we have to get back to the Constitution – and don’t you dare add anything to or take away from that near-divine document (at least in the minds of some). Some go on to say, “The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ is nowhere to be found, so don’t try to add it.”

Okay, let’s go back to the Constitution.

Never once does it use the words “God,” “Jesus,” “Christian,” “Creator,” or even “Nature.” And yet, so many of the “take America back for God,” try to put those words there.

Notice what it does say under Article VI:

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.

And yet, so often we put our political candidates to religious tests. So much for going back to the Constitution.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The Constitution does say that it seeks “to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

Union. Common. General Welfare. Ourselves. Our Posterity.

It seems that these word all have to do everybody, not just some, and definitely not just individuals, despite the use of the phrase, “individual rights,” that is often thrown around (in fact, “individual” is not even a word used in the Constitution).

We have a long ways to go, but in my estimation, in terms of action, we are more Christian today than in the past. We are at a better place now of looking out for the needs of at least most. More people are included in the experience of liberty than in the past. Sure, we don’t use the so-called Christian words as much, but even Jesus criticized folks who said one thing and did another. You’ll know them by their fruit.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Galatians 5:13 For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters; only do not use your freedom as an opportunity for self-indulgence, but through love become slaves to one another. (NRSV)

Philippians 2: 3 Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. 4 Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others. (NRSV)

Matthew 7:20 Thus you will know them by their fruits. (NRSV)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

I initially intended this post to be a book review of Gregory A. Boyd’s book noted above, but I veered in a different direction. Simply put, I recommend that book to anyone interested in and concerned about politics in our country in relation to religion. I don’t agree with everything he says, but for the most part, I think he hits the nail on the head.